How can medical students learn about human anatomy without the aid of a cadaver? How has our understanding of anatomy and physiology changed over time as discoveries, such as the advent of the microscope, have allowed scientists to probe deeper into the human body, extending beyond even the level of a single cell? How have medical instruments and our understanding of disease evolved not only within our modern world, in which new information is assimilated and communicated to the academic community on almost a moment by moment basis, but also within the span of centuries? These are just a few of the questions evoked by the exhibits at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine’s 2017 Anatomy Day. Anatomy Day is an annual event in which medical students are invited to view materials from the Health Sciences Library Special Collections in order to form connections between their experiences in the gross anatomy lab and historical representations of human anatomy.

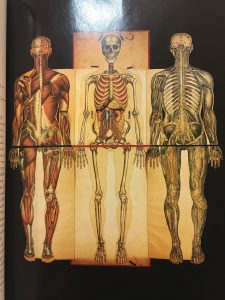

Anatomical models and medical instruments from several centuries were displayed at the Anatomy Day exhibit. Life-sized folding portfolios of anatomical models from the late 19th century, which could be unfolded to reveal the layers of the circulatory system, muscular system, nervous system, and major bones and organs, were available for medical students to compare to the models and cadavers from which modern students learn anatomy.

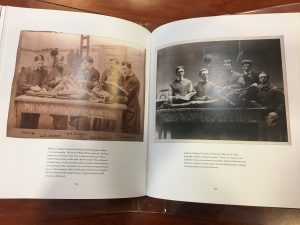

Students were also invited to peruse a book of early 20th century photographs of medical students performing dissections, in which the dissecting tables were often inscribed with epigraphs such as “We have shuffled off his mortal coil” and “The Lord giveth, we taketh away.”

Medical sketches by Dr. Frank H. Netter, who wanted to become an artist but was forced by his parents to attend medical school as a more “practical” career choice, were also on display. Netter practiced during the height of the Great Depression and was unable to make a living as a doctor, so he returned to his passion for art and received a commission to create sketches of various medical abnormalities and procedures that were included in many pamphlets and books.

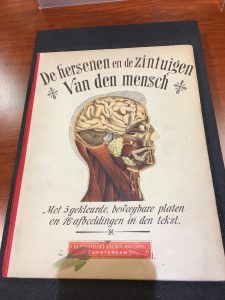

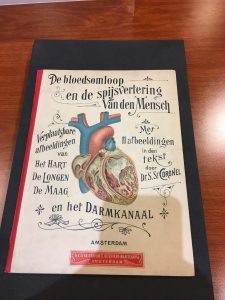

Attendees were also encouraged to examine flap books illustrated by Samuel Coronel in 1898, which depicted “the brain and senses of man” and the circulatory and digestive systems, and to compare them to the recent anatomical models that they study in class.

The rare materials from the Health Sciences Library Special Collections fostered interesting discussions among students and elicited new queries regarding our changing understanding of the human anatomy and how the manner in which we are taught manifests itself in our perceptions of the human body and its physiology.

Emily Long is a double major in Biology and English and a double minor in Chemistry and Medicine, Literature, and Culture.