In a presentation titled “Disability Studies & Health Humanities,” Dr. Kym Weed examined the social construction of disability and how undertones of the eugenics movement exist in today’s COVID-19 emergency care rationing system. To begin her talk, Weed challenged the idea that disability is a purely physical phenomenon based on objective medical standards; instead, she explained disability as “a social product rather than a physical impairment” since the “impairment doesn’t become a disability until [one] can’t participate in society.” Using the example of a person with an amputated leg, Weed explained that this person’s physical impairment only becomes a disability when he or she is unable to access spaces due to steep stairs, no wheelchair ramps, or a lack of elevators. The problem is not the person with the physical impairment, but the way the environment was constructed to be inaccessible for the person. Based on this example, Weed challenged the audience to reexamine how they view disability as something innately wrong with an individual that requires “fixing.” Instead of fixing the individual, Weed suggested the environment could be fixed to be more barrier-free. Ultimately, Weed’s example suggests that the very category of “disabled” should be perceived less as a fact but rather as a description contingent on social and cultural factors subject to change.

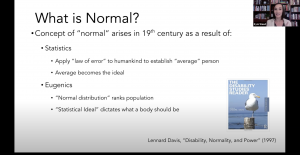

Using this social model to explain disability, Weed proceeded to look at the history of the common understanding of “normal,’ since “we cannot have the concept of disability without the concept of normal.” The elevation of the status of “normal” in modern society occurred in the 19th century following the rise of statistical analysis. As population data was collected on a mass scale, being average on the bell curve distribution became the ideal. This average represented a composite identity that held great power in society by constituting what the human body should be. Rising in popularity around the same time, the Eugenics movement reinforced this concept by moralizing deviance from average and sterilizing those who fell outside arbitrarily defined norms. In addition to causing harm through forced medical interventions, the eugenics movement created violence through stigmatization, marginalization, and discrimination.

Using this social model to explain disability, Weed proceeded to look at the history of the common understanding of “normal,’ since “we cannot have the concept of disability without the concept of normal.” The elevation of the status of “normal” in modern society occurred in the 19th century following the rise of statistical analysis. As population data was collected on a mass scale, being average on the bell curve distribution became the ideal. This average represented a composite identity that held great power in society by constituting what the human body should be. Rising in popularity around the same time, the Eugenics movement reinforced this concept by moralizing deviance from average and sterilizing those who fell outside arbitrarily defined norms. In addition to causing harm through forced medical interventions, the eugenics movement created violence through stigmatization, marginalization, and discrimination.

Weed pointed out that eugenics is not a historical anomaly and that the “logic that fuels eugenics persists today.” By necessitating medical decisions in a resource-limited environment, the COVID-19 pandemic reveals how eugenic logic exists in modern-day health policy. For example, Alabama’s disaster preparedness plan states that people with severe mental retardation, advanced dementia, or severe traumatic brain injury may be poor candidates for ventilator support. Although not explicitly stated, this policy implies these lives are valued less than others and that resources should instead be directed to more “normal” individuals. Weed then shared a powerful example of Michael Hickson, a quadriplegic man who contracted COVID-19 yet was not given a ventilator or advanced care because of his “poor quality of life.” This medical bias against people with disabilities, rooted in our society’s negative value-judgment of their differences, mirrors the same eugenic logic of the past. While any system of medical rationing will be forced to make difficult calls about how to prioritize treatment, there are far more equitable ways to delegate care and resources than the systems described above. UNC Hospitals recently adopted the University of Pittsburgh’s policy for allocating scarce critical care resources, which has been praised by the medical community for its ethical framework and emphasis on not excluding disadvantaged community members from accessing support. As this is literally a matter of life or death, it’s time for more health systems to re-evaluate their decision-making factors for triage care and stop perpetuating this injustice.

Leana is a senior at UNC-Chapel Hill pursuing an undergraduate degree in Health Policy and Management and two minors in Medical Anthropology and Medicine, Literature, and Culture. She is interested in the intersection between social and health policy, research on the social determinants of health, and equitable access to healthcare.